Today I reached up to put some folded laundry on the top shelf of a closet and as I was pulling my arm down I hit my elbow - hard - on the shelf below. I learned two thing in that moment. First, putting laundry away is not worth so much trouble. Second, I will absolutely and despite best intentions use the F-word in front of Emmaline in certain scenarios. Unfortunate, but true.

So my elbow hurt, but of course I knew it was fairly unlikely that I would have broken it under such conditions. I had not been thrown from a horse or a snowboard or gone head over tea kettle down a set of stairs. I would be fine.

But I wasn't fine. I was hurting. True, it was only when I actually moved the elbow, or held something in my hand, but still it was enormously unpleasant.

I took a closer look. There was the beginning of some bruising, which I thought was entirely to be expected. But the elbow in question, my right, was essentially the same size as the one I had on the other side. The lack of impressive swelling made a break much more unlikely. I pushed on all the bits of bone and nothing crunched. I did, however, have quite a lot of tenderness over the olecranon. True, that might just be part of the whole bruise thing, but it could also mean a break. Not a horrible one, but still something that should not be ignored.

I gave it some time and I kept poking myself intermittently, which did nothing to help with the pain. I could pick up Emmaline (reassuring) but it hurt more than a little bit. Hours went by. I complained to my mother. I complained to my father. I complained in front of Emmaline and the dog, but I'm not sure either of them were really listening. Then, Daryl got home from work, and I complained to him.

Did I need to go to the ER and get an x-ray? Did I need a splint and an appointment with an orthopedist just in case? I didn't think so, but I wasn't one hundred percent sure. What if I did nothing and my elbow froze in some weird angle and my mother had to help me get my shirts on and off for the rest of my life?

Twelve hours passed.

"If you were in the ER seeing patients and you came in to see you, what would you say?" Daryl finally asked me. "What would you do?"

I paused and didn't answer.

"Have you even taken ibuprofen?" he asked.

I left the room.

"Whatever," I yelled back.

But I headed for the medicine cabinet. I shook out the pills. Miraculously, less than thirty minutes later, I feel much better. Just don't tell Daryl that.

28 February 2011

27 February 2011

Preventive Care

Last week I wrote about the preponderance of viral gastroenteritis in the community and encouraged young people everywhere to take the revolutionary step of washing their hands. Apparently this was such news that it was picked up by Boston's Universal Hub. I went on to suggest that it is not, in fact, such an unusual occurrence for children to get sick and that we, as parents and health care providers, are faced with the not particularly heroic and in fact rather mundane task of simply seeing them through to the other end.

In the course of seven days time this basic tenet has not really changed. Still, I do have to admit that not all kids get better, even from these sorts of viral illnesses that naturally run their course. Hence the need for ERs and IVs and nurses who can, metaphorically speaking, get blood even out of a stone.

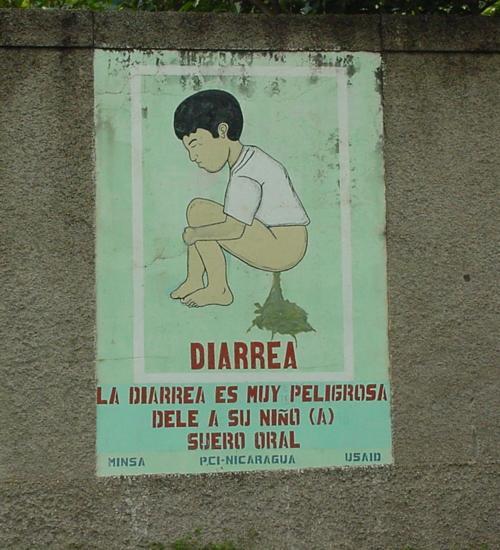

An example. A four-year-old boy is brought into an Emergency Room with the usual vomiting and diarrhea that we all by now know is going around. Mom tells the story with her eye locked on her knees. She refuses to look up.

"What's going on?" I finally ask her.

"He's going to get dehydrated," she says. "It's always the same. You doctors say, 'He looks good, he looks good' and then you send us home. He's just going to get worse."

The problem, I only slowly discovered, was that this little boy had been hospitalized with dehydration during a similar illness two years before. As his symptoms progressed, he was seen by several doctors. They saw that he looked well. They treated his nausea, they encouraged mom to carefully give liquids. They sent him home. Later, when he no longer looked good, they again did the right thing. They treated him with IV fluids. They kept him in the hospital. Then, when he looked better, they let him go.

Mom's assumption was that if he had been treated with an IV at the beginning of his illness, the hospitalization might have been avoided. I looked over the notes. I saw that it was extremely unlikely that this was true. I tried to tell her this in the most honest way I knew how, pointing out that he had been sick in between and had perked up without an IV. Mom nodded, but did not seem to agree. There was no more I could say without seeming to blindly be supporting the medical field in general and so I put the past behind us and got back to the task of making my patient feel better on that day.

I treated her son with oral medicine. When he ate chili cheese fries and then vomited again, he got an IV. When mom and dad said they didn't believe they could care for him at home, he got admitted. When a family is telling me that they are overwhelmed, I generally listen. In the cases where I have not, the patient usually just comes back later. This was a lesson I learned quickly.

So I learned something from this little boy. He stayed in the hospital a short while, got better, went home. There was a lesson to be learned by his parents as well, though I am not sure they were ready to absorb it. First, cheese laden french fries are generally not the best food for a child with a stomach bug. But also, and more importantly, doctors are rarely in charge. We cannot control the course of all illnesses. We hope children will get better. They generally do. We count on their parents to watch them closely and to bring them back in if things start to look worse or simply fail to improve.

And yes, this sometimes asks of parents that they make many trips to their doctor's offices or ERs before a virus takes the turn for the better. Yes, I know this is cruel and unusual punishment for a family trying to take care of a sick child. On the other hand, I also know it would be worse to stick IVs in every child who threw up even once or had diarrhea. It would be worse to keep children who were eating and drinking in a strange hospital overnight.

The way we do things, with small gentle moves that rely heavily on parents to tell us when things do not go as hoped for, is not perfect. I promise when I invent a crystal ball equipped to see the future I will use it wisely and almost entirely for good. Until then, a little patience on all our parts may just be the best that we can do.

In the course of seven days time this basic tenet has not really changed. Still, I do have to admit that not all kids get better, even from these sorts of viral illnesses that naturally run their course. Hence the need for ERs and IVs and nurses who can, metaphorically speaking, get blood even out of a stone.

An example. A four-year-old boy is brought into an Emergency Room with the usual vomiting and diarrhea that we all by now know is going around. Mom tells the story with her eye locked on her knees. She refuses to look up.

"What's going on?" I finally ask her.

"He's going to get dehydrated," she says. "It's always the same. You doctors say, 'He looks good, he looks good' and then you send us home. He's just going to get worse."

The problem, I only slowly discovered, was that this little boy had been hospitalized with dehydration during a similar illness two years before. As his symptoms progressed, he was seen by several doctors. They saw that he looked well. They treated his nausea, they encouraged mom to carefully give liquids. They sent him home. Later, when he no longer looked good, they again did the right thing. They treated him with IV fluids. They kept him in the hospital. Then, when he looked better, they let him go.

Mom's assumption was that if he had been treated with an IV at the beginning of his illness, the hospitalization might have been avoided. I looked over the notes. I saw that it was extremely unlikely that this was true. I tried to tell her this in the most honest way I knew how, pointing out that he had been sick in between and had perked up without an IV. Mom nodded, but did not seem to agree. There was no more I could say without seeming to blindly be supporting the medical field in general and so I put the past behind us and got back to the task of making my patient feel better on that day.

I treated her son with oral medicine. When he ate chili cheese fries and then vomited again, he got an IV. When mom and dad said they didn't believe they could care for him at home, he got admitted. When a family is telling me that they are overwhelmed, I generally listen. In the cases where I have not, the patient usually just comes back later. This was a lesson I learned quickly.

So I learned something from this little boy. He stayed in the hospital a short while, got better, went home. There was a lesson to be learned by his parents as well, though I am not sure they were ready to absorb it. First, cheese laden french fries are generally not the best food for a child with a stomach bug. But also, and more importantly, doctors are rarely in charge. We cannot control the course of all illnesses. We hope children will get better. They generally do. We count on their parents to watch them closely and to bring them back in if things start to look worse or simply fail to improve.

And yes, this sometimes asks of parents that they make many trips to their doctor's offices or ERs before a virus takes the turn for the better. Yes, I know this is cruel and unusual punishment for a family trying to take care of a sick child. On the other hand, I also know it would be worse to stick IVs in every child who threw up even once or had diarrhea. It would be worse to keep children who were eating and drinking in a strange hospital overnight.

The way we do things, with small gentle moves that rely heavily on parents to tell us when things do not go as hoped for, is not perfect. I promise when I invent a crystal ball equipped to see the future I will use it wisely and almost entirely for good. Until then, a little patience on all our parts may just be the best that we can do.

26 February 2011

The Fat Duck

If I had married Daryl for only his cooking, I would not have been disappointed. I grew up subsisting primarily on American cheese and cold hot dogs. When I was a toddler my mother was reduced to peeling my grapes, picking off each tacky layer of skin with her fingernails because she was afraid I would starve and she herself would be dragged in by Child Protective Services to answer questions about why my ribs were so prominent, why my knees so cartoonishly knobby.

My predilection for highly processed sugars and grains has continued to this day and causes my husband no small amount of chagrin. He would do better with Emmaline than he had done with me, he promised even before she popped out of my belly. He would teach her from a young age what good food tasted like.

Early on in our dating there was a night in a pub in the City Centre of Oxford - there were many such nights - and someone asked one of those oldest and most cliched of questions: If you were stranded on a desert island, who would you want with you? And my future husband looked at me across the rickety table cluttered with pint glasses and beer mats with such love in his eyes that my cliche ridden heart literally melted and he said, "It's totally between you and Heston Blumenthal."

So Emmaline has, from a very young age, been offered very complex foods in hopes of inspiring the development of a finer palate than I will ever be able to attain. She has dined on lobster bisque and sesame seared tuna, curried cauliflower and asparagus with Hollandaise. Not all of these have been accepted on first offering, but she has on the whole done remarkably well.

I would not have predicted it. But tonight she didn't flinch when Daryl heaped in front of her a pile of Thai ginger noodles that he scooped out of the wok. She picked one up and went for it. And to be a good role model, I did the same.

25 February 2011

Harriet Lane

Emmaline has taken to walking around the house carrying a copy of the Harriet Lane Handbook: a manual for pediatric house officers. She cries when you take it away. She carefully pulls it off the shelf when you ask her to pick out a book. She flips through the graphs of normal hemoglobin values and glomerular filtration rates intently examining the pages and every once and a while exclaiming, "Oh!"

It is adorable, as is her predilection for rearranging the Tupperware in the kitchen cabinets and for offering her milk to the battered Cabbage Patch Kid from my own childhood before taking a sip of her own. When I mentioned this behavior to a friend she laughed and suggested that Emmaline would be far ahead of her classmates when it came time for her to do a residency of her own. I smiled in response but inwardly I balked. Did I want Emmaline to be a doctor?

My own parents never gave my brother or I any indication of what professions they might have dreamed for us when we were young. They managed to be excited about the things we were excited about, even if those passions fizzled and morphed over the course of a few short days or weeks. When I needed to do an experiment for my science class, my mother gave up her record player so that my crop of mung beans could spin continuously next to their motionless control counterparts. When I came home from watching a Star Trek marathon at a friend's house with a phone number to call for information on Space Camp (1-800-63-SPACE), they let me order the brochure and eventually put me on a plane to Alabama even though they could barely afford to do so.

So ultimately I know that Emmaline will choose her own path. Daryl may have a point that being a female plumber or electrician might be a choice niche market and have the added benefit of not requiring the outlay of college tuition on our part. Of course he has a point. But that doesn't stop me from telling him to shut up.

Still, if she chose medicine, would I be one hundred percent not-at-all-conflicted happy about it?

Bob, one of the techs I work with in the ER asked me last week if I like my job. The brief answer is that I do, much of the time. But the real answer is much more complicated.

When I was in college I read ahead for each of my classes. I wrote papers ahead of time in order to be able to edit them at a leisurely pace, to never feel rushed. I went to bed at a reasonable hour so as to be rested and best able to approach my work for the coming day. It felt better to be in control, to not be playing catch up.

Needless to say, I might have been more fun. I might have had more fun. But I had enough. The same was true in medical school. I worked hard. I crashed and burned on a few quizzes early on and I learned quickly what was expected.

And now I work in a job where it is never possible to entirely know what is expected. I'm sure the same is true of any job to some degree. Expectations change, deadlines shift, we have to be adaptable in order to get ahead. But Daryl, when he goes to work and stays late and finishes things early, he gets to revel in that feeling of accomplishment. There is always more work waiting, to be sure, but there are discreet tasks he can check off and pat himself on the back for powering through.

Things don't work that way in the ER. I have no way to pace myself or control my day because I never know what will be coming in the door. Even those doctors who work in offices face the same problem. A patient placed in a fifteen or twenty minute slot on their schedule may either have a few straightforward issues that can be quickly dealt with and then sent satisfied and on their way...or the patient may be a train wreck. A morning's worth of train wrecks means that other patients wait and that doctor, through absolutely no fault of his own, is stuck playing catch up. Did I mention I hate that?

I suppose this is the way things work any time you work with people instead of paper. The trade off is that I sometimes get hugs when I have finished with a patient. I doubt my husband will ever be offered such affections from the patent clerk he hands his applications over to. So yes, I might worry for Emmaline's happiness should she choose to embark upon a career in medicine twenty years from now. She will have sleepless nights on call, days when she feels she will never know enough to do the job well, moments when patients or their families will take their frustrations out on her simply because she is the bearer of bad news. I won't be able to control any of that. But I can be there to pick up the phone when she calls to talk it over. I suppose that will have to be enough.

Unless, of course, she wants to be a plumber.

It is adorable, as is her predilection for rearranging the Tupperware in the kitchen cabinets and for offering her milk to the battered Cabbage Patch Kid from my own childhood before taking a sip of her own. When I mentioned this behavior to a friend she laughed and suggested that Emmaline would be far ahead of her classmates when it came time for her to do a residency of her own. I smiled in response but inwardly I balked. Did I want Emmaline to be a doctor?

My own parents never gave my brother or I any indication of what professions they might have dreamed for us when we were young. They managed to be excited about the things we were excited about, even if those passions fizzled and morphed over the course of a few short days or weeks. When I needed to do an experiment for my science class, my mother gave up her record player so that my crop of mung beans could spin continuously next to their motionless control counterparts. When I came home from watching a Star Trek marathon at a friend's house with a phone number to call for information on Space Camp (1-800-63-SPACE), they let me order the brochure and eventually put me on a plane to Alabama even though they could barely afford to do so.

So ultimately I know that Emmaline will choose her own path. Daryl may have a point that being a female plumber or electrician might be a choice niche market and have the added benefit of not requiring the outlay of college tuition on our part. Of course he has a point. But that doesn't stop me from telling him to shut up.

Still, if she chose medicine, would I be one hundred percent not-at-all-conflicted happy about it?

Bob, one of the techs I work with in the ER asked me last week if I like my job. The brief answer is that I do, much of the time. But the real answer is much more complicated.

When I was in college I read ahead for each of my classes. I wrote papers ahead of time in order to be able to edit them at a leisurely pace, to never feel rushed. I went to bed at a reasonable hour so as to be rested and best able to approach my work for the coming day. It felt better to be in control, to not be playing catch up.

Needless to say, I might have been more fun. I might have had more fun. But I had enough. The same was true in medical school. I worked hard. I crashed and burned on a few quizzes early on and I learned quickly what was expected.

And now I work in a job where it is never possible to entirely know what is expected. I'm sure the same is true of any job to some degree. Expectations change, deadlines shift, we have to be adaptable in order to get ahead. But Daryl, when he goes to work and stays late and finishes things early, he gets to revel in that feeling of accomplishment. There is always more work waiting, to be sure, but there are discreet tasks he can check off and pat himself on the back for powering through.

Things don't work that way in the ER. I have no way to pace myself or control my day because I never know what will be coming in the door. Even those doctors who work in offices face the same problem. A patient placed in a fifteen or twenty minute slot on their schedule may either have a few straightforward issues that can be quickly dealt with and then sent satisfied and on their way...or the patient may be a train wreck. A morning's worth of train wrecks means that other patients wait and that doctor, through absolutely no fault of his own, is stuck playing catch up. Did I mention I hate that?

I suppose this is the way things work any time you work with people instead of paper. The trade off is that I sometimes get hugs when I have finished with a patient. I doubt my husband will ever be offered such affections from the patent clerk he hands his applications over to. So yes, I might worry for Emmaline's happiness should she choose to embark upon a career in medicine twenty years from now. She will have sleepless nights on call, days when she feels she will never know enough to do the job well, moments when patients or their families will take their frustrations out on her simply because she is the bearer of bad news. I won't be able to control any of that. But I can be there to pick up the phone when she calls to talk it over. I suppose that will have to be enough.

Unless, of course, she wants to be a plumber.

24 February 2011

Closet Full of Hats

I heard the screaming even before I the door banged open to let Daryl and Emmaline in from outside.

Then I heard Daryl call out, "Meg, we've got a little bit of blood here."

There's this thing that happens when children are crying and have blood in their mouths where the blood mixes with spit and snot and tears until the usually angelic toddler is transformed into a virtual Hannibal Lecter. So Emmaline was not especially beautiful after falling flat on her face from our shallow front concrete step.

I took her from Daryl. I gave her a hug. I played the mom for about thirty seconds and then I wanted to see what was wrong.

Daryl was taking off his coat instead of getting a washcloth to wipe up the blood. Maybe he was doing the dad thing, where you hand the baby off, take a deep breath, and hope there is nothing else you will be called on to do. When I asked for the washcloth Daryl's arms were still twisted and caught up in the sleeves of his jacket. My mom went to the drawer and ran the hot water and handed the moist towel to me.

"Take her," I told Daryl, now free of his parka.

He sat Em facing me in his arms and I wiped at the blood, transforming her from one of the FBIs Most Wanted serial killers into a beautiful baby girl. She was still crying, of course. There was still snot on her face, but then I wiped that up to.

It was at this point that I became obsessed with the location of her top two front teeth. Now Emmaline, like her mommy and daddy before her, does not have remarkably straight teeth. They have been, since erupting, slightly askew. But were they slightly more so after her fall? Had they been pushed up into the permanent teeth above them, forever damaging her adult smile? Did she need a trip to the Children's Emergency Room to see a pediatric dentist and get panoramic x-rays of her entire jaw? Did her front teeth need to be yanked back and splinted in place with spackle and glue?

The bleeding had stopped only minutes after her accident. She was happily chewing on a cracker and asking for milk. Any sane person would have looked at their child and seen immediately that she was okay. But I am not sane. I am a pediatrician. And so we spent the following several hours, she and I, in a power struggle where I tried all of the most cunning techniques my years in practice have provided me to get a good look in a small child's mouth and she simply and resolutely decided not to let me.

Would she, if her teeth had shifted significantly and dangerously, so cavalierly eaten a cracker? Would she have chewed on the block that she quickly picked up? A rational person would say, no. But I was not being rational.

People assume that because I am a doctor for very small human beings that I must automatically parent better or easier because of the things that I know. There are times that is probably true. When Emmaline got her first sniffly nose cold at a few months of age she sounded atrocious. The snot rattled around in the back of her throat and she kept us awake. But her lungs were clear. I knew this because I own a stethoscope and I had checked. So when Daryl, in the middle of the night, became alarmed at the decibel level of her breathing, I asked, "Is she blue?" When he assured me that she was not, I rolled over and went right back to sleep.

There are times when the things I have seen in the hospital or in the clinic do make it easier to step back and decide there is no need to actually panic. The first time Emmaline fell and bumped her head, for example, and the second and the third and so on and so forth. But there are also time when I think that I panic more.

Did Emma enjoy having her mother pry her mouth open on multiple occasions during the course of that afternoon? Did she need me (when she was about six months old) to spend twenty-four hours looking at pictures of abnormally shaped heads while trying to decide if her sutures had closed prematurely? Would she enjoy knowing that I put off getting her treated for croup (and making her more comfortable) when she was a little over a year because I was satisfied she was not sick enough to actually die?

I'm guessing the answer to all of this questions is no. I'm guessing that in the future whenever she might be posed with such a query, she would rather I stop playing doctor and remember to just be her mom.

Then I heard Daryl call out, "Meg, we've got a little bit of blood here."

There's this thing that happens when children are crying and have blood in their mouths where the blood mixes with spit and snot and tears until the usually angelic toddler is transformed into a virtual Hannibal Lecter. So Emmaline was not especially beautiful after falling flat on her face from our shallow front concrete step.

I took her from Daryl. I gave her a hug. I played the mom for about thirty seconds and then I wanted to see what was wrong.

Daryl was taking off his coat instead of getting a washcloth to wipe up the blood. Maybe he was doing the dad thing, where you hand the baby off, take a deep breath, and hope there is nothing else you will be called on to do. When I asked for the washcloth Daryl's arms were still twisted and caught up in the sleeves of his jacket. My mom went to the drawer and ran the hot water and handed the moist towel to me.

"Take her," I told Daryl, now free of his parka.

He sat Em facing me in his arms and I wiped at the blood, transforming her from one of the FBIs Most Wanted serial killers into a beautiful baby girl. She was still crying, of course. There was still snot on her face, but then I wiped that up to.

It was at this point that I became obsessed with the location of her top two front teeth. Now Emmaline, like her mommy and daddy before her, does not have remarkably straight teeth. They have been, since erupting, slightly askew. But were they slightly more so after her fall? Had they been pushed up into the permanent teeth above them, forever damaging her adult smile? Did she need a trip to the Children's Emergency Room to see a pediatric dentist and get panoramic x-rays of her entire jaw? Did her front teeth need to be yanked back and splinted in place with spackle and glue?

The bleeding had stopped only minutes after her accident. She was happily chewing on a cracker and asking for milk. Any sane person would have looked at their child and seen immediately that she was okay. But I am not sane. I am a pediatrician. And so we spent the following several hours, she and I, in a power struggle where I tried all of the most cunning techniques my years in practice have provided me to get a good look in a small child's mouth and she simply and resolutely decided not to let me.

Would she, if her teeth had shifted significantly and dangerously, so cavalierly eaten a cracker? Would she have chewed on the block that she quickly picked up? A rational person would say, no. But I was not being rational.

People assume that because I am a doctor for very small human beings that I must automatically parent better or easier because of the things that I know. There are times that is probably true. When Emmaline got her first sniffly nose cold at a few months of age she sounded atrocious. The snot rattled around in the back of her throat and she kept us awake. But her lungs were clear. I knew this because I own a stethoscope and I had checked. So when Daryl, in the middle of the night, became alarmed at the decibel level of her breathing, I asked, "Is she blue?" When he assured me that she was not, I rolled over and went right back to sleep.

There are times when the things I have seen in the hospital or in the clinic do make it easier to step back and decide there is no need to actually panic. The first time Emmaline fell and bumped her head, for example, and the second and the third and so on and so forth. But there are also time when I think that I panic more.

Did Emma enjoy having her mother pry her mouth open on multiple occasions during the course of that afternoon? Did she need me (when she was about six months old) to spend twenty-four hours looking at pictures of abnormally shaped heads while trying to decide if her sutures had closed prematurely? Would she enjoy knowing that I put off getting her treated for croup (and making her more comfortable) when she was a little over a year because I was satisfied she was not sick enough to actually die?

I'm guessing the answer to all of this questions is no. I'm guessing that in the future whenever she might be posed with such a query, she would rather I stop playing doctor and remember to just be her mom.

23 February 2011

Getting "Intensely Personal"

There are a few copies of my book, Between Expectations, floating around the house of late. Now, as tempted as I am to give them away to family, friends, strangers on the street, I am told that is generally not the best way to get people to actually buy copies of the book all by themselves. Nevertheless, my mother did get a hold of a copy and she did pass it on to one of her oldest and dearest friends.

As I was working on updating this site yesterday, my mother walked into the family room waving her phone in front of her.

"You have a fan," she whispered.

"What?" I asked.

"Just take this," she insisted, just about putting the phone up to my ear for me.

"I just finished reading your book," my mother's friend had called to say. "I just need to tell you, I was blown away."

Obviously, it is always fabulous to receive praise. The fact that this was the first person outside my family who has read the book and told me they liked it means a great deal. The people whose quotes decorate the back of the jacket cover read it, they wrote nice things to my publisher, but they never called me up on the phone. I won't hold that against them. I'm guessing Samuel Shem has more important things to do.

So needless to say, this was a moment when it began to feel a little more real to me. The book will be out in just about a week. Bookstores are going to stock it. Even small bookstores, like the one my husband and I took Emmaline to last night to play. I know this because I made Daryl go to the desk and ask if it was in stock. I did this even knowing that talking to strangers is something he hates.

"It's not out yet," he reminded me.

"I know that," I told him. "You know that. But they don't know that you know that. Just go ask. Please, please, please."

So he did. It was not yet in stock - surprise, surprise - but it would be on March 1.

The other thing that has made this feel real to me is the copy of the book I put into a padded envelope and addressed to the parents of one of my patients who died when I was in training. There are parts of the book that are about him. His parents will read it, I hope. They will feel things - good, bad, everything in between - I don't know what things. But what if it hurts them to read?

And even though I wrote the book with as much tenderness and awe as I knew how to, I find myself worrying, what if it's not enough?

It might not be. In fact, it probably isn't. Because how could I - who knew their son for a month, who knew all of these children that I wrote about for only a brief moment in time - know enough to write down anything of meaning about the experiences they went through? I can't.

But still, I had to try.

And even though there is a big part of me that is scared of what people will think when they finally do read it, afraid people will know at last how selfish and petty and stupid I often am, I realize that I have to be brave. Not really brave. Not "I'm going to stick a needle in your arm and maybe one in your back and make you stay in the hospital" brave. I only need to be a little bit brave and then the book will be out and people can read about all of the little children who are so much braver than I will ever be. So, yes, that's something I can do. Wish me luck.

As I was working on updating this site yesterday, my mother walked into the family room waving her phone in front of her.

"You have a fan," she whispered.

"What?" I asked.

"Just take this," she insisted, just about putting the phone up to my ear for me.

"I just finished reading your book," my mother's friend had called to say. "I just need to tell you, I was blown away."

Obviously, it is always fabulous to receive praise. The fact that this was the first person outside my family who has read the book and told me they liked it means a great deal. The people whose quotes decorate the back of the jacket cover read it, they wrote nice things to my publisher, but they never called me up on the phone. I won't hold that against them. I'm guessing Samuel Shem has more important things to do.

So needless to say, this was a moment when it began to feel a little more real to me. The book will be out in just about a week. Bookstores are going to stock it. Even small bookstores, like the one my husband and I took Emmaline to last night to play. I know this because I made Daryl go to the desk and ask if it was in stock. I did this even knowing that talking to strangers is something he hates.

"It's not out yet," he reminded me.

"I know that," I told him. "You know that. But they don't know that you know that. Just go ask. Please, please, please."

So he did. It was not yet in stock - surprise, surprise - but it would be on March 1.

The other thing that has made this feel real to me is the copy of the book I put into a padded envelope and addressed to the parents of one of my patients who died when I was in training. There are parts of the book that are about him. His parents will read it, I hope. They will feel things - good, bad, everything in between - I don't know what things. But what if it hurts them to read?

And even though I wrote the book with as much tenderness and awe as I knew how to, I find myself worrying, what if it's not enough?

It might not be. In fact, it probably isn't. Because how could I - who knew their son for a month, who knew all of these children that I wrote about for only a brief moment in time - know enough to write down anything of meaning about the experiences they went through? I can't.

But still, I had to try.

And even though there is a big part of me that is scared of what people will think when they finally do read it, afraid people will know at last how selfish and petty and stupid I often am, I realize that I have to be brave. Not really brave. Not "I'm going to stick a needle in your arm and maybe one in your back and make you stay in the hospital" brave. I only need to be a little bit brave and then the book will be out and people can read about all of the little children who are so much braver than I will ever be. So, yes, that's something I can do. Wish me luck.

22 February 2011

See, Do, Teach

A few weeks ago I had a medical student see a patient for me in the Emergency Room. Even at first glance you could tell she was clever, and it wasn’t only the uniform of her short white coat – the hem falling just below her slim hips, its pockets full to brimming with flash cards and highlighters and even a copy ofPreTest weeks before she would be required to take her Pediatrics shelf exam. Instead it was the way she moved her hand across the piece of paper she had just set down on the desk between us, smoothing its crinkled edges, pressing her palm firmly against the lines of ink as if for reassurance, before beginning her presentation.

The piece of paper itself was remarkable, an entire 8x11 sheet filled with meticulous print, the distillation of the patient’s seventeen years of cheerleading injuries, occasional headaches, and a gassy intolerance for dairy into a sort of cribsheet, a collection of glyphs indecipherable to anyone but she. It was far more than was required. This statement (were I to say it to her face) would not be a compliment, would in fact be a warning, constructive criticism meant to hone her skills for triaging, for moving through a story from the onset of illness to the moment the patient walks through the doors of the ER as quickly as possible, in the space of only a few minutes while still missing nothing of import. There were times when she would disappear into a room and fail to emerge until I had seen and discharged one or two other patients, at which point the nurses would shake their heads and say, “Don’t you dare ever do that to me.”

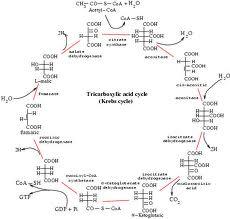

Because most medical students - despite having committed to memory all of the intimate details of the Krebs cycle and gluconeogenesis and structure of essential and non-essential amino acids - start out incredibly bad at this job.

There are seminars during the first and second year of training that are meant to slowly introduce us to the act of interviewing a patient, sitting in the room across from a stranger and asking them (sensitively, encouragingly, patiently) to divulge the most intimate details of their private life. These courses are also meant to familiarize us with the general work flow of a hospital - how to write orders, access medical records, find the cafeteria quickly in order make it back to the OR in time to scrub in to another cholecystectomy during which you will move the laparoscopic camera a little to the left and a little to the right and then back again.

Still there is nothing that can fully prepare you for the responsibilities you must assume when you start your third year of medical school, or your first year of residency, or your life as an attending. When I was in college my mother frequently insisted I spend more time in the hospital, believing this would somehow help me divine whether or not this was my true calling. But being there isn't the hard part. It's not how you react to the smells and the sounds - many of which are more than a little unpleasant - that determine whether you will make it through. It's how you react to the feelings of helplessness. It's how quickly you replace these with moments of acumen. And how easily you can identify the difference between the two.

This process is especially difficult in pediatrics. How do you learn to suture or poke needles into a miniature human being? Who do you practice on except other miniature human beings? And what parents would line up for that honor? Would I knowingly let inexperienced hands touch Emmaline?

I understand the hesitation. But I also know that without allowing medical students to perform these procedures in carefully supervised scenarios, they may graduate never having performed a lumbar puncture or placed a suture. I did. And will it be any easier for those parents to allow the same inexperienced hands to touch their children once they are in residency? I have colleagues who have become attendings (supervising doctors) out in practice on their own who are placed in situations where they have to do a procedure they have never done before and by this time there is no one there to help them.

So when the teenager from a group home came in to have his cheek stitched back up again I placed the first few stitches and then I handed the needle driver to my sidekick. I let my med student finish the repair.

I was teaching, which is part of my job. But I felt conflicted doing it. After all, the patient I had chosen did not have his parents there. He had guardians from his group home, but this is hardly the same thing. I worried (even though I could very easily have taken out any stitches I did not like the look of) that I was treating him like a second class citizen because he was in shackles. But my student did a wonderful job. He was a bit slower than I might have been but our patient was patient and did not seem to mind.

So then I worried that I was doing a disservice to my medical student by assuming that the care he could provide, which was excellent, was in any way second class. It wasn't.

He practiced beforehand, he took instruction graciously, and he did a wonderful job. We worked as a team and brought the edges of the cut neatly together so that it will barely leave a scar.

And that, by any definition, is a job well done.

Living the Dream (originally 21 February 2011)

I've met up with several friends recently and the question of when to have a second child seems to be on everyone's mind. Unlike our parents' generation we did not get married and have kids right out of high school or college. We dawdled along this path to adulthood, gathering up graduate degrees like candy from the bulk barrels at the supermarket - one from here, one from there - moving on to get real jobs far later in life than my own parents ever thought possible.

The reward for this sort of childish perseverance was supposed to be a steady job, a good paycheck, a house with an outrageous mortgage, maybe a pet or two. As my friends and I finally settled into this pattern baby pictures started popping up on Facebook. We picked out strollers. We struggled with decision about daycare. Then a couple years went by (or seventeen months in the case of Emmaline).

I thought we had it figured out. It's unfortunate that 10% of our monthly budget goes to paying my student loans, but that's the cost of doing business as they say. Take a deep breath and move on.

But then my friends started saying they weren't sure they could afford another child. Not one friend, not two. Many. And not a third or fourth child. A second.

How is it possible that smart people, hard working people, people who have gone to schools like Harvard and Princeton and Yale and Stanford and who have gotten jobs as doctors and lawyers and business administrators are so strapped for cash on a month to month basis that they are not sure there will be enough left over to see the next munchkin fed and clothed and housed?

Times are tough, certainly. We moved into one or two bedroom apartments. Maybe we even bought these as condos. The market crashed. Our salaries stagnated. The home that was meant to be temporary starts to be a little more permanent. So these friends, these people who get up and go to work every day at jobs they spent years becoming qualified for, are reassessing just what it means to have enough.

Enough toys - fewer to pick up, I say. Enough clothes - require less drawer space, one might suggest. Enough space - the more the merrier, our parents might have believed.

Many of us did share bedrooms when we were younger. But it's not the way we assumed we would operate when we had our own children. Why? Where is it written that you need a four bedroom house in the suburbs in order to have your 2.4 kids?

Is this why the new average number of children per households is only 1.83?

Demographics change for a number of reasons and there are many factors that contribute to that trend.

Birth control, at least until the Republican Congress has finished waging it's war against women, is more available than it once was. Houses are expensive. Daycare is expensive. We all know these things to be true. Having strong armed my own parents into early retirement to rescue us from this very dilemma I cannot pretend that there is any easy answer. But neither do I think we necessarily need to give up the dream entirely if that dream includes another child, only readjust it a bit.

In the meantime, might I suggest bunk beds. I think bunk beds could really be fun.

The reward for this sort of childish perseverance was supposed to be a steady job, a good paycheck, a house with an outrageous mortgage, maybe a pet or two. As my friends and I finally settled into this pattern baby pictures started popping up on Facebook. We picked out strollers. We struggled with decision about daycare. Then a couple years went by (or seventeen months in the case of Emmaline).

I thought we had it figured out. It's unfortunate that 10% of our monthly budget goes to paying my student loans, but that's the cost of doing business as they say. Take a deep breath and move on.

But then my friends started saying they weren't sure they could afford another child. Not one friend, not two. Many. And not a third or fourth child. A second.

How is it possible that smart people, hard working people, people who have gone to schools like Harvard and Princeton and Yale and Stanford and who have gotten jobs as doctors and lawyers and business administrators are so strapped for cash on a month to month basis that they are not sure there will be enough left over to see the next munchkin fed and clothed and housed?

Times are tough, certainly. We moved into one or two bedroom apartments. Maybe we even bought these as condos. The market crashed. Our salaries stagnated. The home that was meant to be temporary starts to be a little more permanent. So these friends, these people who get up and go to work every day at jobs they spent years becoming qualified for, are reassessing just what it means to have enough.

Enough toys - fewer to pick up, I say. Enough clothes - require less drawer space, one might suggest. Enough space - the more the merrier, our parents might have believed.

Many of us did share bedrooms when we were younger. But it's not the way we assumed we would operate when we had our own children. Why? Where is it written that you need a four bedroom house in the suburbs in order to have your 2.4 kids?

Is this why the new average number of children per households is only 1.83?

Demographics change for a number of reasons and there are many factors that contribute to that trend.

Birth control, at least until the Republican Congress has finished waging it's war against women, is more available than it once was. Houses are expensive. Daycare is expensive. We all know these things to be true. Having strong armed my own parents into early retirement to rescue us from this very dilemma I cannot pretend that there is any easy answer. But neither do I think we necessarily need to give up the dream entirely if that dream includes another child, only readjust it a bit.

In the meantime, might I suggest bunk beds. I think bunk beds could really be fun.

Reality Check (originally 20 February 2011)

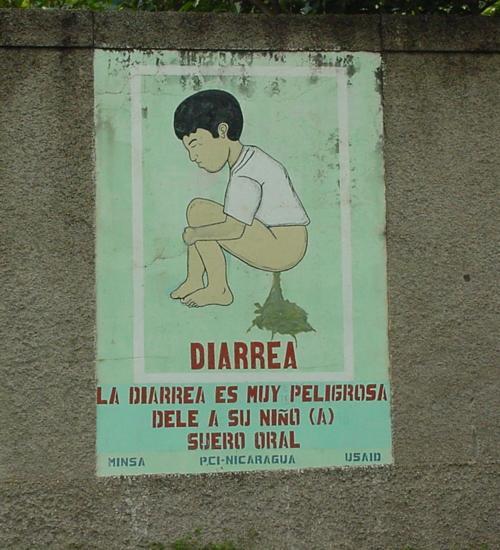

I saw twenty-seven patients during a shift earlier this week and fifteen or so were throwing up and having diarrhea. So please, consider this your public service announcement to WASH YOUR HANDS. Repeatedly.

I typically pump the Purell dispenser on my way into a room, talk to the family and patient, step out of the room to pump it again, do my exam, talk to the family some more, make a plan, step out of the room, pump the dispenser one last time, move to the next patient and start the cycle again. That might seem obsessive. And to tell you I have not yet contracted the dreaded gastro might seem like laughing into the faces of the Gods who are currently sending this pestilence down upon the land. I realize this. So this week I did what I usually do but also stuck my hand under the Purell dispenser a couple of times during my exam (while moving from the abdomen to check the ears) and at every single dispenser whenever I walked down the hall and back to my office.

Kids do catch GI bugs this time of year, but typically speaking it is not quite this many. We have been busy. This mini-outbreak of norovirusus or rotavirus or whatever it is comes on top of the usual wheezing and coughing and sniffles that are the bread and butter of the winter season in a children's ER. One mother was so distressed by the vomiting and frequent smelly diaper changes that I felt I had to ask her, "Has your child ever been sick before?" And the answer was no.

Now I'm sure this three-year-old had suffered the usual sniffles and, yes, there is something terribly violent about the act of throwing up - the gagging, the tears before and after, the slightly faded look of a child who is tired and ill - but I couldn't help but think she was having a bit of an overreaction.

She was concerned about her daughter. That part was entirely appropriate. She tenderly wiped the girl's hair back away from her forehead as she settled back on the exam bed to watch Pocahontas. She wanted to see her daughter feel better. Again, what mother would not? But there was another level entirely to her frenetic energy. There was the assumption that her child should not be ill. She said this several ways and on more than one occasion during the hour or so the girl sat with us in the ER.

"How could this have happened?"

There's something going around would have been an accurate if somewhat clichéd explanation. And I did say this to her, as I said it to all of the parents who came in that night. There is always something going around.

Here's how it works, according to the Centers for Disease Control:

GI bugs are "transmitted primarily through the fecal-oral route, either by consumption of fecally contaminated food or water or by direct person-to-person spread. Environmental and fomite contamination may also act as a source of infection. Good evidence exists for transmission [of some viruses] due to aerosolization of vomitus that presumably results in droplets contaminating surfaces or entering the oral mucosa and being swallowed."

Now I did not say to this mother, or any other, "Your child probably touched something or someone that touched poop." Because that's gross. We are lucky enough to live in a country with generally excellent sanitation systems, so why would we think about such things? But maybe we ought to.

Kids are supposed to get sick. People assume just the opposite. It is why they shake their heads and say, "It must be so hard to be a pediatrician. It must be so hard to see all those sick kids."

Sure. No one likes to see small adorable creatures suffer. There are children who become very ill, who have diseases that keep them for months in the hospital and make them have test after test and procedure after procedure and, yes, watching this happen (to a child who the week before had been practicing riding his bike without training wheels) does hurt. It does cause physical pain.

The other kids - the ones who get runny noses or puke their brains out for a few days and then go back to riding that bike - I feel sorry for, but I also know that this is absolutely the way the world works and one hundred percent to be expected. I help them as much as I can. I send them home or up to the inpatient ward to get better. And they do get better. Here. In this place of easy access to IV fluids and zofran and other sundry perks of our oft criticized healthcare system. Kids get better.

There are things you can do too.

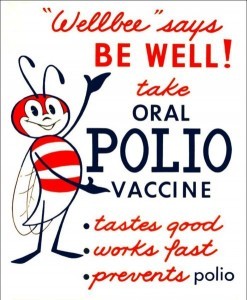

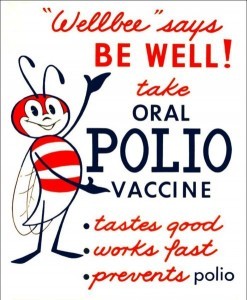

Wash your hands. Vaccinate your children. Do what you can to stop the spread of these diseases. Give a few dollars to Unicef or Rotary International and help Bill Gates in his goal to eradicate polio. What's that, you ask? It's something we don't have in the country because we are lucky enough to have good access to immunizations, but it's something that kills and paralyzes children who are not so privileged.

And then, when you take your exhausted child home from the ER to feed them popsicles or sips of juice, try to take a moment between the diaper changes and wiping up puke to remember that it's really not all that bad. It's part of being human and a parent. It's awful for a while, but then the toddler who never let's you hold her when she's not sick because she's so busy stacking blocks and painting pictures and making messes actually falls asleep in your arms. And then it's totally worth it.

I typically pump the Purell dispenser on my way into a room, talk to the family and patient, step out of the room to pump it again, do my exam, talk to the family some more, make a plan, step out of the room, pump the dispenser one last time, move to the next patient and start the cycle again. That might seem obsessive. And to tell you I have not yet contracted the dreaded gastro might seem like laughing into the faces of the Gods who are currently sending this pestilence down upon the land. I realize this. So this week I did what I usually do but also stuck my hand under the Purell dispenser a couple of times during my exam (while moving from the abdomen to check the ears) and at every single dispenser whenever I walked down the hall and back to my office.

Kids do catch GI bugs this time of year, but typically speaking it is not quite this many. We have been busy. This mini-outbreak of norovirusus or rotavirus or whatever it is comes on top of the usual wheezing and coughing and sniffles that are the bread and butter of the winter season in a children's ER. One mother was so distressed by the vomiting and frequent smelly diaper changes that I felt I had to ask her, "Has your child ever been sick before?" And the answer was no.

Now I'm sure this three-year-old had suffered the usual sniffles and, yes, there is something terribly violent about the act of throwing up - the gagging, the tears before and after, the slightly faded look of a child who is tired and ill - but I couldn't help but think she was having a bit of an overreaction.

She was concerned about her daughter. That part was entirely appropriate. She tenderly wiped the girl's hair back away from her forehead as she settled back on the exam bed to watch Pocahontas. She wanted to see her daughter feel better. Again, what mother would not? But there was another level entirely to her frenetic energy. There was the assumption that her child should not be ill. She said this several ways and on more than one occasion during the hour or so the girl sat with us in the ER.

"How could this have happened?"

There's something going around would have been an accurate if somewhat clichéd explanation. And I did say this to her, as I said it to all of the parents who came in that night. There is always something going around.

Here's how it works, according to the Centers for Disease Control:

GI bugs are "transmitted primarily through the fecal-oral route, either by consumption of fecally contaminated food or water or by direct person-to-person spread. Environmental and fomite contamination may also act as a source of infection. Good evidence exists for transmission [of some viruses] due to aerosolization of vomitus that presumably results in droplets contaminating surfaces or entering the oral mucosa and being swallowed."

Now I did not say to this mother, or any other, "Your child probably touched something or someone that touched poop." Because that's gross. We are lucky enough to live in a country with generally excellent sanitation systems, so why would we think about such things? But maybe we ought to.

Kids are supposed to get sick. People assume just the opposite. It is why they shake their heads and say, "It must be so hard to be a pediatrician. It must be so hard to see all those sick kids."

Sure. No one likes to see small adorable creatures suffer. There are children who become very ill, who have diseases that keep them for months in the hospital and make them have test after test and procedure after procedure and, yes, watching this happen (to a child who the week before had been practicing riding his bike without training wheels) does hurt. It does cause physical pain.

The other kids - the ones who get runny noses or puke their brains out for a few days and then go back to riding that bike - I feel sorry for, but I also know that this is absolutely the way the world works and one hundred percent to be expected. I help them as much as I can. I send them home or up to the inpatient ward to get better. And they do get better. Here. In this place of easy access to IV fluids and zofran and other sundry perks of our oft criticized healthcare system. Kids get better.

There are things you can do too.

Wash your hands. Vaccinate your children. Do what you can to stop the spread of these diseases. Give a few dollars to Unicef or Rotary International and help Bill Gates in his goal to eradicate polio. What's that, you ask? It's something we don't have in the country because we are lucky enough to have good access to immunizations, but it's something that kills and paralyzes children who are not so privileged.

And then, when you take your exhausted child home from the ER to feed them popsicles or sips of juice, try to take a moment between the diaper changes and wiping up puke to remember that it's really not all that bad. It's part of being human and a parent. It's awful for a while, but then the toddler who never let's you hold her when she's not sick because she's so busy stacking blocks and painting pictures and making messes actually falls asleep in your arms. And then it's totally worth it.

Zionism (originally 16 February 2011)

In 1984 Libby Zion, a teenager in New York, died shortly after being admitted to the hospital. The doctors who cared for her that night were overextended and likely overtired. Libby's father was angered by the possibility that his daughter's death might have been prevented had staffing at the hospital been different. The media coverage and ensuing court case were the impetus behind New York State's Bell Commission Report, which as of 1989 would regulate resident work hours for the very first time.

Residents would be allowed to work for no more than 80 hours a week and 30 hours at a time. No longer allowed were the afternoon clinics that might stretch to 7 or 8 on the day after you got up and came to work. The ACGME (American College of Graduate Medical Education) enacted similar reforms nationwide in 2003. By the time I was an intern in 2006 the system was still riddled with kinks, but it was widely accepted. On non-call days I came into the hospital to pre-round at 6 or 6:30 and stayed (ideally) until 5 or 6. Every fourth day I would come to work, then work overnight, then go home the next day at around 1pm. Weekends were the same.

My final year in residency my parents and my in laws still did not understand this. Monday: work. Tuesday: work. Wednesday: work until Thursday. Friday: work again.

I don't do this any more. I don't do anything close. But walking the floors of the hospital today, avoiding the bizarre robots that wheel themselves along the halls moving paper or medical records from place to place, I am still tired. I am tired enough to wonder how my friends who are still residents and those young doctors in our training program whom I've never met, I wonder how they are surviving.

I've run into a few still-resident friends today and they all have smiles on their faces. So I don't think those years are as bleak as I sometimes remember them being. But still they are hard. I had to write a book to wrap my head around how hard and even so I don't have it entirely figured out.

For those of you with children or brothers or sisters or friends or husbands or wives who are doing their residency training right now, remember it's not their fault they've forgotten about you. There were times when I was so tired I couldn't remember my own name. And also remember, it does get better. It actually gets rather wonderful.

Residents would be allowed to work for no more than 80 hours a week and 30 hours at a time. No longer allowed were the afternoon clinics that might stretch to 7 or 8 on the day after you got up and came to work. The ACGME (American College of Graduate Medical Education) enacted similar reforms nationwide in 2003. By the time I was an intern in 2006 the system was still riddled with kinks, but it was widely accepted. On non-call days I came into the hospital to pre-round at 6 or 6:30 and stayed (ideally) until 5 or 6. Every fourth day I would come to work, then work overnight, then go home the next day at around 1pm. Weekends were the same.

My final year in residency my parents and my in laws still did not understand this. Monday: work. Tuesday: work. Wednesday: work until Thursday. Friday: work again.

I don't do this any more. I don't do anything close. But walking the floors of the hospital today, avoiding the bizarre robots that wheel themselves along the halls moving paper or medical records from place to place, I am still tired. I am tired enough to wonder how my friends who are still residents and those young doctors in our training program whom I've never met, I wonder how they are surviving.

I've run into a few still-resident friends today and they all have smiles on their faces. So I don't think those years are as bleak as I sometimes remember them being. But still they are hard. I had to write a book to wrap my head around how hard and even so I don't have it entirely figured out.

For those of you with children or brothers or sisters or friends or husbands or wives who are doing their residency training right now, remember it's not their fault they've forgotten about you. There were times when I was so tired I couldn't remember my own name. And also remember, it does get better. It actually gets rather wonderful.

Cabin Fever (originally 15 February 2011)

Maybe it was the $1500 heating bill, maybe a subtle sign of vitamin D deficiency, but either way I am fed up with winter. Last fall my supervisor insisted I buy a small plastic slide for Emmaline's first birthday.

I mentioned that I expected we would get plenty of use out of it even during the winter since our front hall is big enough to double as a playground. She was horrified.

"The slide goes outside," she decreed. "Every day, no matter the weather, you bundle the baby up and you take her out to play in the yard."

I nodded because, well, that's what you do when your boss seems so sure of something. But the slide stayed indoors.

Ultimately, this is the only reason I still know where the slide is. I had a backyard.

I bought a house with grass and trees and, yes, a strange retaining wall that is absolutely a safety hazard that will need to be addressed just as soon as we can find it again. Then the yard went away.

The snow outside the windows comes as high as my chest. The kitchen door opens just enough to let the dog escape, run up the icy embankment, and look down at those of us still held captive with unparalleled joy.

Emmaline, for whom the house must have seemed like a mansion after moving from our old condo, launched a full on protest today. She pushed her stroller out of the hall, across the dining room, and into the kitchen. I watched with amusement as she circumnavigated the puppy, managing to avoid the stained glass fireplace screen, and arrived with the pram at the back door.

Even though I had not heeded my supervisor's advice to the letter, I am all in favor of sunshine and fresh air. It's not as though I didn't want to take her out. But after a well deserved lull in the frigid temperatures yesterday during which the height of the snowbanks along our driveway became appreciably diminished, it is once again well below freezing. Moreover, and this is the real reason there was no way Em was getting her way, we seemed to be in the middle of a wind storm. Branches were flying off trees, the windows rattled as they were buffeted. I shook my head in an apology.

"Sorry baby," I said. "You can still have a ride."

I hoisted her up and plopped her into the carriage chair, then reclined it and pulled the sun shade making a sort of cocoon. She stuck her thumb in her mouth. We made a circuit around the kitchen and back to the front of the house.

"Out?" I asked when we had finished, not realizing what it seemed I was offering.

"Out," said Emmaline.

But when I moved to pick her up, when I pushed back her shade and reached for her she screamed. It took me several tries to arrive at my mistake.

"Up?" I then tried instead.

"No," she told me.

So I left her where she was. I hung a sheet over the remaining opening at the front so that she was enclosed entirely.

"Tent," I said.

I walked away, wondering if she would nap.

"Mama," she called.

"Emma," I called back.

"Mama," she answered.

And so on and so forth.

She never did fall asleep but she refused to leave her tent for thirty minutes at least.

When the wind died down we did get some outdoors time. Not much, but enough.

Still I am looking forward to spring. There are two-hundred bulbs (minus those liberated by squirrels) in the front yard that my calloused thumbs and I deserve to see push up through the ground. We're still a long way from that day. I do know that. But it is nice to remember warmer times.

And also to know that Em is ready for them to come again. She's even got the shades to prove it.

I mentioned that I expected we would get plenty of use out of it even during the winter since our front hall is big enough to double as a playground. She was horrified.

"The slide goes outside," she decreed. "Every day, no matter the weather, you bundle the baby up and you take her out to play in the yard."

I nodded because, well, that's what you do when your boss seems so sure of something. But the slide stayed indoors.

Ultimately, this is the only reason I still know where the slide is. I had a backyard.

I bought a house with grass and trees and, yes, a strange retaining wall that is absolutely a safety hazard that will need to be addressed just as soon as we can find it again. Then the yard went away.

The snow outside the windows comes as high as my chest. The kitchen door opens just enough to let the dog escape, run up the icy embankment, and look down at those of us still held captive with unparalleled joy.

Emmaline, for whom the house must have seemed like a mansion after moving from our old condo, launched a full on protest today. She pushed her stroller out of the hall, across the dining room, and into the kitchen. I watched with amusement as she circumnavigated the puppy, managing to avoid the stained glass fireplace screen, and arrived with the pram at the back door.

Even though I had not heeded my supervisor's advice to the letter, I am all in favor of sunshine and fresh air. It's not as though I didn't want to take her out. But after a well deserved lull in the frigid temperatures yesterday during which the height of the snowbanks along our driveway became appreciably diminished, it is once again well below freezing. Moreover, and this is the real reason there was no way Em was getting her way, we seemed to be in the middle of a wind storm. Branches were flying off trees, the windows rattled as they were buffeted. I shook my head in an apology.

"Sorry baby," I said. "You can still have a ride."

I hoisted her up and plopped her into the carriage chair, then reclined it and pulled the sun shade making a sort of cocoon. She stuck her thumb in her mouth. We made a circuit around the kitchen and back to the front of the house.

"Out?" I asked when we had finished, not realizing what it seemed I was offering.

"Out," said Emmaline.

But when I moved to pick her up, when I pushed back her shade and reached for her she screamed. It took me several tries to arrive at my mistake.

"Up?" I then tried instead.

"No," she told me.

So I left her where she was. I hung a sheet over the remaining opening at the front so that she was enclosed entirely.

"Tent," I said.

I walked away, wondering if she would nap.

"Mama," she called.

"Emma," I called back.

"Mama," she answered.

And so on and so forth.

She never did fall asleep but she refused to leave her tent for thirty minutes at least.

When the wind died down we did get some outdoors time. Not much, but enough.

Still I am looking forward to spring. There are two-hundred bulbs (minus those liberated by squirrels) in the front yard that my calloused thumbs and I deserve to see push up through the ground. We're still a long way from that day. I do know that. But it is nice to remember warmer times.

And also to know that Em is ready for them to come again. She's even got the shades to prove it.

That Feeling Deep Inside (originally 14 February 2011)

I recently sent an email to some colleagues at the hospitals where I work promising one lucky winner an advance copy of my book, Between Expectations, available now on Amazon and soon in bookstores everywhere in exchange for their thoughts on love. Now this was a shameless self-promotional plug, the equivalent of screaming on a street corner, "I wrote a book! Please, please notice me!". But it was not as shameless or self-promotional as Valentine's Day is for companies like Hallmark. So I did not ask their thoughts on love of the existential, Dawson's Creekvariety. Rather I asked what were those presenting complaints that bring a patient into the hospital or Emergency Room that make them scramble to claim that patient as their own.

I expected disagreement on the subject. Surely there would be some inherent personalilty traits that would make particular doctors or nurses excited by the broken femur but repulsed by the vomiting and vice versa. I never expected an overwhelming consensus, but I got one.

What is that one thing, that tantalizing mystery, that compells more medical personnel to elbow interns and residents out of their way in order to be the first person into a patient's room than any other? Simply put, Foreign Body.

Remember, I do not take care of adults. When children stick something where it does not belong it is not gross. It is adorable.

A few examples may help me make my case. A six-year-old walks into an ER. She woke to find she must have swallowed one of her teeth, which the day prior had been loose. It was not in her bedding. It was not on the floor. She was distraught, in a frenzy, convinced that it was stuck in her throat. It was not. She still would not stop crying.

"What's wrong, sweetie," her treating physician asked, kneeling before her.

"Will the Tooth Fairy still come?"

My own patient, years ago, an eight-year-old with a bead in each ear. She had misunderstood a magic trick in which she was supposed to hide the beads behind her ears, not in them, and now she could not get them out. I looked (one was pink, one was blue) and determined I could easily retrieve them. But first I left her room to present to my attending, like the good little resident I was then, and told him the story. He went in to look for himself and confirm my assessment. When he came out he had the beads with him.

Now this particular attending is actually a very good teacher. On other occasions he had helped me to perform a sundry of other procedures. So I have often wondered what possessed him to pilfer an intervention of so little acuity, something he had likely done countless times while I myself had had the opportunity to do only a few. Now I understand that he just couldn't help himself. It was beyond his control. Love makes you powerless. I get that now.

This is not only a recent phenomenon. Last weekend in Chicago my husband noticed that one of the balls in a clear plastic box his parents had on a living room shelf - a game that you tilt and shake in attempts to coax the balls into the shallow depressions on the bottom of their enclosure - was black instead of silver.

"Does this open?" he asked. "One of these is different from the others."

"It's not supposed to open," my father-in-law told him, "but one of your cousins got into it anyway and then swallowed a ball."

There was a pause. My husband took a deep breath.

"And you replaced the ball with this black one?"

"No," his father told him, "it had turned black by the time it came out."

My husband pursed his lips and put the game back on the shelf.

Then, earlier this week, our local news had a story on a puppy who had swallowed a foot long drumstick (the musical sort, not from poultry) that needed to be surgically removed. Scout slept angelically on the daybed next to me.

"Wake up," I said, shaking her. "Pay attention. This is why you don't chew on things that are not yours."

But it was no use. By the end of the night we had lost yet another stuffed creature, this time a cow, to her ferocious puppy jaws. There were tiny dollops of silicone and gossamer trails of stuffing all over the dining room floor. Then, the following morning, there were two piles of steaming dog poo behind the kitchen and right at eye level since we have had so much snow. These too were decorated as if with sugary sprinkles and it took me some time to realize that they were the same silicone pearls I had swept up so many of the night before.

"Better out than in," I said rather cavalierly.

In reality, though, I had been more than a little crazy when the cow went missing since it had magnets in each of its four little legs. If Scout swallowed more than one of them, or if they were left on the floor and Emmaline ingested them, then that was an emergency. Click they might go, across the wall of the dog's bowel.Click they might say, ripping a hole in my baby's ileum. So, yes, I spent more than a few minutes sifting through the carnage underneath the dining room table, ensuring that I had found every last one.

Still this brush with disaster did not make me any less gleeful when I was called the following day about a young patient who had swallowed part of a necklace.

"Send her over," I told the referring physician. "We'll see where it is."

We did. It had passed safely out of her chest and into her stomach, obviating the need for any intervention. I showed her the films. Then I sent her home with x-rays in tow so she could show each and every one of her friends the things she had deep inside.

I expected disagreement on the subject. Surely there would be some inherent personalilty traits that would make particular doctors or nurses excited by the broken femur but repulsed by the vomiting and vice versa. I never expected an overwhelming consensus, but I got one.

What is that one thing, that tantalizing mystery, that compells more medical personnel to elbow interns and residents out of their way in order to be the first person into a patient's room than any other? Simply put, Foreign Body.

Remember, I do not take care of adults. When children stick something where it does not belong it is not gross. It is adorable.

A few examples may help me make my case. A six-year-old walks into an ER. She woke to find she must have swallowed one of her teeth, which the day prior had been loose. It was not in her bedding. It was not on the floor. She was distraught, in a frenzy, convinced that it was stuck in her throat. It was not. She still would not stop crying.

"What's wrong, sweetie," her treating physician asked, kneeling before her.

"Will the Tooth Fairy still come?"

My own patient, years ago, an eight-year-old with a bead in each ear. She had misunderstood a magic trick in which she was supposed to hide the beads behind her ears, not in them, and now she could not get them out. I looked (one was pink, one was blue) and determined I could easily retrieve them. But first I left her room to present to my attending, like the good little resident I was then, and told him the story. He went in to look for himself and confirm my assessment. When he came out he had the beads with him.

Now this particular attending is actually a very good teacher. On other occasions he had helped me to perform a sundry of other procedures. So I have often wondered what possessed him to pilfer an intervention of so little acuity, something he had likely done countless times while I myself had had the opportunity to do only a few. Now I understand that he just couldn't help himself. It was beyond his control. Love makes you powerless. I get that now.

This is not only a recent phenomenon. Last weekend in Chicago my husband noticed that one of the balls in a clear plastic box his parents had on a living room shelf - a game that you tilt and shake in attempts to coax the balls into the shallow depressions on the bottom of their enclosure - was black instead of silver.

"Does this open?" he asked. "One of these is different from the others."

"It's not supposed to open," my father-in-law told him, "but one of your cousins got into it anyway and then swallowed a ball."

There was a pause. My husband took a deep breath.

"And you replaced the ball with this black one?"

"No," his father told him, "it had turned black by the time it came out."

My husband pursed his lips and put the game back on the shelf.

Then, earlier this week, our local news had a story on a puppy who had swallowed a foot long drumstick (the musical sort, not from poultry) that needed to be surgically removed. Scout slept angelically on the daybed next to me.

"Wake up," I said, shaking her. "Pay attention. This is why you don't chew on things that are not yours."

But it was no use. By the end of the night we had lost yet another stuffed creature, this time a cow, to her ferocious puppy jaws. There were tiny dollops of silicone and gossamer trails of stuffing all over the dining room floor. Then, the following morning, there were two piles of steaming dog poo behind the kitchen and right at eye level since we have had so much snow. These too were decorated as if with sugary sprinkles and it took me some time to realize that they were the same silicone pearls I had swept up so many of the night before.

"Better out than in," I said rather cavalierly.