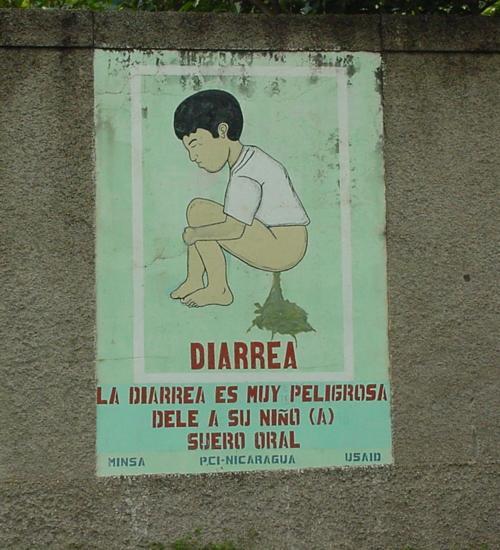

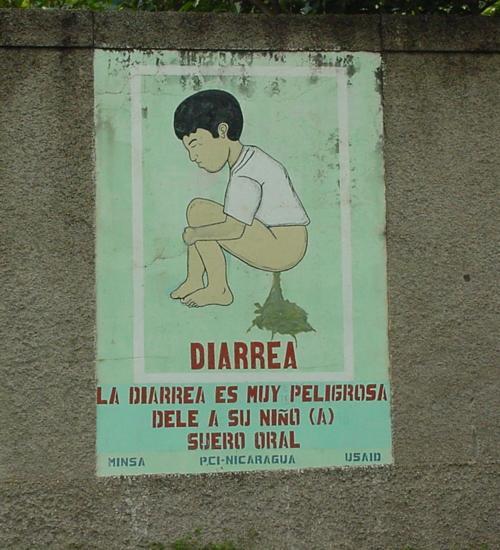

I saw twenty-seven patients during a shift earlier this week and fifteen or so were throwing up and having diarrhea. So please, consider this your public service announcement to WASH YOUR HANDS. Repeatedly.

I typically pump the Purell dispenser on my way into a room, talk to the family and patient, step out of the room to pump it again, do my exam, talk to the family some more, make a plan, step out of the room, pump the dispenser one last time, move to the next patient and start the cycle again. That might seem obsessive. And to tell you I have not yet contracted the dreaded gastro might seem like laughing into the faces of the Gods who are currently sending this pestilence down upon the land. I realize this. So this week I did what I usually do but also stuck my hand under the Purell dispenser a couple of times during my exam (while moving from the abdomen to check the ears) and at every single dispenser whenever I walked down the hall and back to my office.

Kids do catch GI bugs this time of year, but typically speaking it is not quite this many. We have been busy. This mini-outbreak of norovirusus or rotavirus or whatever it is comes on top of the usual wheezing and coughing and sniffles that are the bread and butter of the winter season in a children's ER. One mother was so distressed by the vomiting and frequent smelly diaper changes that I felt I had to ask her, "Has your child ever been sick before?" And the answer was no.

Now I'm sure this three-year-old had suffered the usual sniffles and, yes, there is something terribly violent about the act of throwing up - the gagging, the tears before and after, the slightly faded look of a child who is tired and ill - but I couldn't help but think she was having a bit of an overreaction.

She was concerned about her daughter. That part was entirely appropriate. She tenderly wiped the girl's hair back away from her forehead as she settled back on the exam bed to watch Pocahontas. She wanted to see her daughter feel better. Again, what mother would not? But there was another level entirely to her frenetic energy. There was the assumption that her child should not be ill. She said this several ways and on more than one occasion during the hour or so the girl sat with us in the ER.

"How could this have happened?"

There's something going around would have been an accurate if somewhat clichéd explanation. And I did say this to her, as I said it to all of the parents who came in that night. There is always something going around.

Here's how it works, according to the Centers for Disease Control:

GI bugs are "transmitted primarily through the fecal-oral route, either by consumption of fecally contaminated food or water or by direct person-to-person spread. Environmental and fomite contamination may also act as a source of infection. Good evidence exists for transmission [of some viruses] due to aerosolization of vomitus that presumably results in droplets contaminating surfaces or entering the oral mucosa and being swallowed."

Now I did not say to this mother, or any other, "Your child probably touched something or someone that touched poop." Because that's gross. We are lucky enough to live in a country with generally excellent sanitation systems, so why would we think about such things? But maybe we ought to.

Kids are supposed to get sick. People assume just the opposite. It is why they shake their heads and say, "It must be so hard to be a pediatrician. It must be so hard to see all those sick kids."

Sure. No one likes to see small adorable creatures suffer. There are children who become very ill, who have diseases that keep them for months in the hospital and make them have test after test and procedure after procedure and, yes, watching this happen (to a child who the week before had been practicing riding his bike without training wheels) does hurt. It does cause physical pain.

The other kids - the ones who get runny noses or puke their brains out for a few days and then go back to riding that bike - I feel sorry for, but I also know that this is absolutely the way the world works and one hundred percent to be expected. I help them as much as I can. I send them home or up to the inpatient ward to get better. And they do get better. Here. In this place of easy access to IV fluids and zofran and other sundry perks of our oft criticized healthcare system. Kids get better.

There are things you can do too.

Wash your hands. Vaccinate your children. Do what you can to stop the spread of these diseases. Give a few dollars to Unicef or Rotary International and help Bill Gates in his goal to eradicate polio. What's that, you ask? It's something we don't have in the country because we are lucky enough to have good access to immunizations, but it's something that kills and paralyzes children who are not so privileged.

And then, when you take your exhausted child home from the ER to feed them popsicles or sips of juice, try to take a moment between the diaper changes and wiping up puke to remember that it's really not all that bad. It's part of being human and a parent. It's awful for a while, but then the toddler who never let's you hold her when she's not sick because she's so busy stacking blocks and painting pictures and making messes actually falls asleep in your arms. And then it's totally worth it.

I typically pump the Purell dispenser on my way into a room, talk to the family and patient, step out of the room to pump it again, do my exam, talk to the family some more, make a plan, step out of the room, pump the dispenser one last time, move to the next patient and start the cycle again. That might seem obsessive. And to tell you I have not yet contracted the dreaded gastro might seem like laughing into the faces of the Gods who are currently sending this pestilence down upon the land. I realize this. So this week I did what I usually do but also stuck my hand under the Purell dispenser a couple of times during my exam (while moving from the abdomen to check the ears) and at every single dispenser whenever I walked down the hall and back to my office.

Kids do catch GI bugs this time of year, but typically speaking it is not quite this many. We have been busy. This mini-outbreak of norovirusus or rotavirus or whatever it is comes on top of the usual wheezing and coughing and sniffles that are the bread and butter of the winter season in a children's ER. One mother was so distressed by the vomiting and frequent smelly diaper changes that I felt I had to ask her, "Has your child ever been sick before?" And the answer was no.

Now I'm sure this three-year-old had suffered the usual sniffles and, yes, there is something terribly violent about the act of throwing up - the gagging, the tears before and after, the slightly faded look of a child who is tired and ill - but I couldn't help but think she was having a bit of an overreaction.

She was concerned about her daughter. That part was entirely appropriate. She tenderly wiped the girl's hair back away from her forehead as she settled back on the exam bed to watch Pocahontas. She wanted to see her daughter feel better. Again, what mother would not? But there was another level entirely to her frenetic energy. There was the assumption that her child should not be ill. She said this several ways and on more than one occasion during the hour or so the girl sat with us in the ER.

"How could this have happened?"

There's something going around would have been an accurate if somewhat clichéd explanation. And I did say this to her, as I said it to all of the parents who came in that night. There is always something going around.

Here's how it works, according to the Centers for Disease Control:

GI bugs are "transmitted primarily through the fecal-oral route, either by consumption of fecally contaminated food or water or by direct person-to-person spread. Environmental and fomite contamination may also act as a source of infection. Good evidence exists for transmission [of some viruses] due to aerosolization of vomitus that presumably results in droplets contaminating surfaces or entering the oral mucosa and being swallowed."

Now I did not say to this mother, or any other, "Your child probably touched something or someone that touched poop." Because that's gross. We are lucky enough to live in a country with generally excellent sanitation systems, so why would we think about such things? But maybe we ought to.

Kids are supposed to get sick. People assume just the opposite. It is why they shake their heads and say, "It must be so hard to be a pediatrician. It must be so hard to see all those sick kids."

Sure. No one likes to see small adorable creatures suffer. There are children who become very ill, who have diseases that keep them for months in the hospital and make them have test after test and procedure after procedure and, yes, watching this happen (to a child who the week before had been practicing riding his bike without training wheels) does hurt. It does cause physical pain.

The other kids - the ones who get runny noses or puke their brains out for a few days and then go back to riding that bike - I feel sorry for, but I also know that this is absolutely the way the world works and one hundred percent to be expected. I help them as much as I can. I send them home or up to the inpatient ward to get better. And they do get better. Here. In this place of easy access to IV fluids and zofran and other sundry perks of our oft criticized healthcare system. Kids get better.

There are things you can do too.

Wash your hands. Vaccinate your children. Do what you can to stop the spread of these diseases. Give a few dollars to Unicef or Rotary International and help Bill Gates in his goal to eradicate polio. What's that, you ask? It's something we don't have in the country because we are lucky enough to have good access to immunizations, but it's something that kills and paralyzes children who are not so privileged.

And then, when you take your exhausted child home from the ER to feed them popsicles or sips of juice, try to take a moment between the diaper changes and wiping up puke to remember that it's really not all that bad. It's part of being human and a parent. It's awful for a while, but then the toddler who never let's you hold her when she's not sick because she's so busy stacking blocks and painting pictures and making messes actually falls asleep in your arms. And then it's totally worth it.

No comments:

Post a Comment