A few weeks ago I had a medical student see a patient for me in the Emergency Room. Even at first glance you could tell she was clever, and it wasn’t only the uniform of her short white coat – the hem falling just below her slim hips, its pockets full to brimming with flash cards and highlighters and even a copy ofPreTest weeks before she would be required to take her Pediatrics shelf exam. Instead it was the way she moved her hand across the piece of paper she had just set down on the desk between us, smoothing its crinkled edges, pressing her palm firmly against the lines of ink as if for reassurance, before beginning her presentation.

The piece of paper itself was remarkable, an entire 8x11 sheet filled with meticulous print, the distillation of the patient’s seventeen years of cheerleading injuries, occasional headaches, and a gassy intolerance for dairy into a sort of cribsheet, a collection of glyphs indecipherable to anyone but she. It was far more than was required. This statement (were I to say it to her face) would not be a compliment, would in fact be a warning, constructive criticism meant to hone her skills for triaging, for moving through a story from the onset of illness to the moment the patient walks through the doors of the ER as quickly as possible, in the space of only a few minutes while still missing nothing of import. There were times when she would disappear into a room and fail to emerge until I had seen and discharged one or two other patients, at which point the nurses would shake their heads and say, “Don’t you dare ever do that to me.”

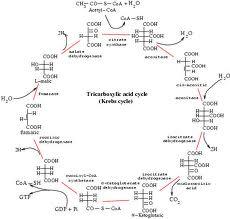

Because most medical students - despite having committed to memory all of the intimate details of the Krebs cycle and gluconeogenesis and structure of essential and non-essential amino acids - start out incredibly bad at this job.

There are seminars during the first and second year of training that are meant to slowly introduce us to the act of interviewing a patient, sitting in the room across from a stranger and asking them (sensitively, encouragingly, patiently) to divulge the most intimate details of their private life. These courses are also meant to familiarize us with the general work flow of a hospital - how to write orders, access medical records, find the cafeteria quickly in order make it back to the OR in time to scrub in to another cholecystectomy during which you will move the laparoscopic camera a little to the left and a little to the right and then back again.

Still there is nothing that can fully prepare you for the responsibilities you must assume when you start your third year of medical school, or your first year of residency, or your life as an attending. When I was in college my mother frequently insisted I spend more time in the hospital, believing this would somehow help me divine whether or not this was my true calling. But being there isn't the hard part. It's not how you react to the smells and the sounds - many of which are more than a little unpleasant - that determine whether you will make it through. It's how you react to the feelings of helplessness. It's how quickly you replace these with moments of acumen. And how easily you can identify the difference between the two.

This process is especially difficult in pediatrics. How do you learn to suture or poke needles into a miniature human being? Who do you practice on except other miniature human beings? And what parents would line up for that honor? Would I knowingly let inexperienced hands touch Emmaline?

I understand the hesitation. But I also know that without allowing medical students to perform these procedures in carefully supervised scenarios, they may graduate never having performed a lumbar puncture or placed a suture. I did. And will it be any easier for those parents to allow the same inexperienced hands to touch their children once they are in residency? I have colleagues who have become attendings (supervising doctors) out in practice on their own who are placed in situations where they have to do a procedure they have never done before and by this time there is no one there to help them.

So when the teenager from a group home came in to have his cheek stitched back up again I placed the first few stitches and then I handed the needle driver to my sidekick. I let my med student finish the repair.

I was teaching, which is part of my job. But I felt conflicted doing it. After all, the patient I had chosen did not have his parents there. He had guardians from his group home, but this is hardly the same thing. I worried (even though I could very easily have taken out any stitches I did not like the look of) that I was treating him like a second class citizen because he was in shackles. But my student did a wonderful job. He was a bit slower than I might have been but our patient was patient and did not seem to mind.

So then I worried that I was doing a disservice to my medical student by assuming that the care he could provide, which was excellent, was in any way second class. It wasn't.

He practiced beforehand, he took instruction graciously, and he did a wonderful job. We worked as a team and brought the edges of the cut neatly together so that it will barely leave a scar.

And that, by any definition, is a job well done.

Nice post.

ReplyDelete